"Something broken or deficient comes more naturally to me. Sometimes that thing is the mind. Sometimes it is the body."

-Hideaki Anno, creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion

"Monsters are tragic beings; they are born too tall, too strong, too heavy, they are not evil by choice. That is their tragedy."

- Ishiro Honda, director of Godzilla

Image via Amazon Prime Video

Horror is born of trauma. The pop-culture monsters we fear and are fascinated by tend to reflect our very real anxieties. Frankenstein tells the story of scientific progress so explosive that it risks leaving humanity behind. It Follows creates a nightmare vision of looming intimacy and the potential for unknowable disease. Leatherface, hooting at the dinner table with his brothers in rural Texas, was the child of economic angst, the crimes of Ed Gein, and of President Nixon's threat of a "silent majority" forcing Americans to reconsider whether or not they really knew their neighbors.

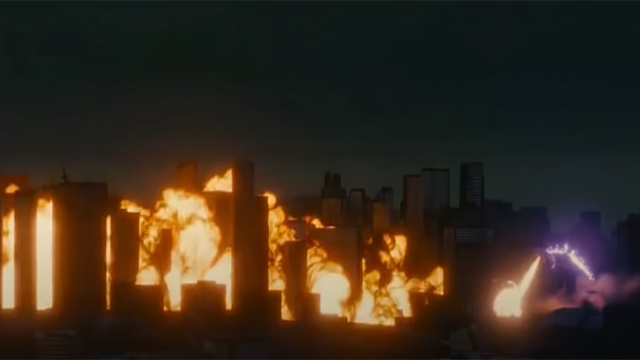

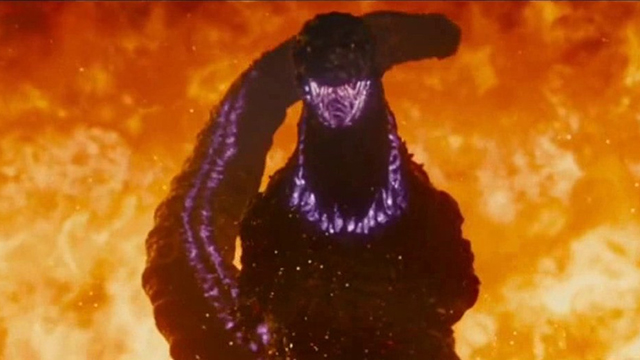

And Godzilla? Well, Godzilla is a metaphor for a bomb. A bunch of bombs, actually. But more important than that, he represents loss — the loss of structure, of prosperity, of control. Godzilla is our own hubris returning to haunt us, the idea that in the end, we are helpless in the face of nature, disaster, and even our own mistakes. We, as a species, woke him up and now we have to deal with him, no matter how unprepared we are.

Hideaki Anno understands this.

In 1993, he began work on Neon Genesis Evangelion, a mecha series profound in not just its depiction of a science fiction world but in its treatment of depression and mental illness. It is a seminal work in the medium of anime, a "must-watch," and it would turn Anno into a legend, though his relationship to his magnum opus remains continuous and, at best, complicated. It is endlessly fascinating, often because Anno seems endlessly fascinated by it.

In 2017, he would win the Japanese Academy Film Prize for Director of the Year for Shin Godzilla, a film that also won Picture of the Year, scored five other awards, and landed 11 nominations in total. Shin Godzilla was the highest-grossing live-action Japanese film of 2016, scoring 8.25 billion yen and beating out big-name imports like Disney's Zootopia. In comparison, the previous Godzilla film, Final Wars, earned 1.26 billion. Shin Godzilla captured the public's attention in a way that most modern films in the franchise had not, returning the King of the Monsters to his terrifying (and culturally relevant roots).

So how did he do it? How did Anno, a titan of the anime industry famous for his extremely singular creations, take a monster that had practically become a ubiquitous mascot of Japanese pop culture and successfully reboot him for the masses? How did Godzilla and Neon Genesis Evangelion align in a way that now there are video games, attractions, and promotions that feature the two franchises cohabitating? The answer is a little more complex than, "Well, they're both pretty big, I guess."

To figure that out, we have to go back to two dates: 1954 and 1993. Though nearly 40 years apart, both find Japan on the tail end of disaster.

Part 1: 1954 and 1993

On August 6th and August 9th 1945, two atomic bombs were dropped on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. These would kill hundreds of thousands of people, serving as tragic codas to the massive air raids already inflicted on the island nation. Six days after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan would surrender to the Allied forces and World War II would officially end. But the fear would not.

Within a year, the South Pacific would become home to many United States-conducted nuclear tests, just a few thousand miles from Japan. And though centered around the Marshall Islands, the chance of an accident was fairly high. And on March 1, 1954, one such accident happened, with the Lucky Dragon #5 fishing boat getting caught in the fallout from a hydrogen bomb test. The crew would suffer from radiation-related illnesses, and radioman Kuboyama Aikichi would die due to an infection during treatment. For many around the world, it was a small vessel in the wrong place at the wrong time. For Japan, it was a reminder that even a decade after their decimation from countless bombs, atomic terror still loomed far too close to home.

Godzilla emerged from this climate. Films about giant monsters had become popular, with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a 1952 re-release of King Kong smashing their way through the box office, and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka wanted to combine aspects of these with something that would comment on anti-nuclear themes. Handed to former soldier and Toho Studios company man Ishiro Honda for direction and tokusatsu wizard Eiji Tsubaraya for special effects, Godzilla took form and would be released a mere eight months after the Lucky Dragon incident.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

It was a success, coming in eighth in the box office for the year and it would lead to dozens of sequels that would see Godzilla go from atomic nightmare to lizard superhero (and then back and forth a few times). America, sensing profits, bought the rights, edited it heavily, inserted Rear Window star Raymond Burr as an American audience surrogate, and released it as Godzilla: King of the Monsters! It was also very profitable, and for the next 20 years, every Japanese Godzilla film got a dubbed American version following soon in its wake.

Years went by. Japan would recover from World War II and the following Allied Occupation and become an economic powerhouse. But in the late '80s, troubling signs began to emerge. An asset price bubble, based on the current economy's success and optimism about the future, was growing. And despite the Bank of Japan's desperate attempts to buy themselves some time, the bubble burst and the stock market plummeted. In 1991, a lengthy, devastating recession now known as the "Lost Decade" started. And the resulting ennui was not just economic but cultural.

The suicide rate rose sharply. Young people, formerly on the cusp of what seemed to be promising careers as "salarymen," found themselves listless and without direction. Disillusionment set in, both with the government and society itself, something still found in Japan today. And though people refusing to engage with the norms of modern culture and instead retreating from it is nothing new in any nation, the demographic that we now know as "Hikikomori" appeared. And among these youths desperate to find something better amid the rubble of a once-booming economy was animator Hideaki Anno.

A co-founder of the anime production company Gainax, Anno was no stranger to depression, having grappled with it his entire life. Dealing with his own mental illness and haunted by the failure of important past projects, Anno made a deal that would allow for increased creative control, and in 1993, began work on Neon Genesis Evangelion. Combining aspects of the popular mech genre with a plot and themes that explored the psyche of a world and characters on the brink of ruin, NGE would become extremely popular, despite a less than smooth production.

The series would concern Shinji Ikari, a fourteen-year-old boy who suffers from depression and anxiety in a broken and terrifying world. Forced to pilot an EVA unit by his mysterious and domineering father, Shinji's story and his relationships with others are equal parts tragic and desperate, and the series provides little solace for its players. Anno would become more interested in psychology as the production of the series went on, and the last handful of episodes reflect this heavily.

Image via Netflix

After the original ending inspired derision and rage from fans, Anno and Gainax would follow it up with two sequel projects (Death & Rebirth and The End of Evangelion), and NGE's place in the pantheon of "classic" anime was set. Paste Magazine recently named it the third-best anime series of all time. IGN has it placed at #8 and the British Film Insititute included End of Evangelion on their list of 50 key anime films. The exciting, thoughtful, and heart-breaking story of Shinji Ikari, Asuka, Minato, and the rest has gone down in history as one of the best stories ever told.

So what would combine the two and bring Godzilla's massive presence under the influence of Anno's masterful hand? As is a miserable trend here, that particular film would also be spawned from catastrophe.

Part 2: 2011

"There was no storm to sail out of: The earth was spasming beneath our feet, and we were pretty much vulnerable as long as we were touching it," said Carin Nakanishi in an interview with The Guardian. The spasm she was referring to? The 2011 Tohoku earthquake, the most powerful earthquake in the history of Japan. Its after-effects would include a tsunami and the meltdown of three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The death toll was in the tens of thousands. The property destruction seemed limitless. The environmental impact was shocking. Naoto Kan, the Japanese Prime Minister at the time, called it the worst crisis for Japan since World War II.

It took years to figure out the full extent of the damage. Four years after, in 2015, 229,000 people still remained displaced from their ruined homes. The radiation in the water was so severe that fisheries were forced to avoid it. The cultivation of local agriculture was driven to a halt, with farmland being abandoned for most of the decade. And though the direct effects of it varied depending on how far away you lived, one symptom remained consistent: The inability to trust those who'd been sworn in to help.

"No useful information was being offered by the government or the media," Nakanishi said. Many voiced a fear that the government had not done its decontamination job properly or would not continue to help them if they returned to their former homes near Fukushima. Some felt the people making decisions were far too distant to truly understand what was going on. Many thought that the government had underestimated the danger. In a survey taken after the Fukushima meltdown, "only 16 percent of respondents ... expressed trust in government institutions." In most of these stories, citizens stepped in to help, feeling as if they had no other choice. Eventually, his approval ratings dropped to only 10 percent and Naoto Kan stepped down from his role as Prime Minister.

And what of Godzilla and Anno at the time? Well, the former lay dormant, having been given a 10-year hiatus from the big screen by Toho after the release of 2004's Godzilla: Final Wars. And though he'd show up in a short sequence in Toho's 2007 film Always Zoku Sanchome no Yuhi, they kept good on their promise. But Godzilla fans did not have to worry about a drought of Godzilla news. American film production company Legendary Pictures was busy formulating their own take on him, having acquired the rights a year before.

Meanwhile, Anno's post Evangelion life consisted of ... a lot more Evangelion. Though he'd direct some live-action films, his most newsworthy project was a series of Rebuild of Evangelion titles, anime films built with different aims (and created with a different mindset) than the original series. Departing Gainax in 2007, these would be created under his newly founded studio, Studio Khara.

Image via Netflix

And while it's obvious from the contents of Evangelion that Anno is interested in giant monsters and giant beings in general (Evangelion is pretty chockful of them), this fascination would only become more open. In 2013, he'd curate a tokusatsu exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, one that showcased miniatures from Mothra to Ultraman to Godzilla himself. About the exhibit, Anno would write:

"As children we grew up watching tokusatsu and anime programs. We were immediately riveted to the sci-fi images and worlds they portrayed. They put us in awe, and made us feel such suspense and excitement. (...) I think our hearts were deeply moved by the grown-ups' earnest efforts working at the sets that dwelled deep behind the images. (...) The emotions and sensations from those cherished moments have lead us to become who we are today."

For the presentation, he'd also produce a short film called A Giant Warrior Descends on Tokyo, with the monster based on a creature from Hayao Miyazaki's — his old boss and an inspiration to Anno, along with the man that Anno would accompany on a trip to the Iwata prefecture to show support for communities wrecked by the Tohoku earthquake — Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind manga. It was directed by Shinji Higuchi, an old collaborator of Anno's at Gainax who had served as Special Effects Director for Shusuke Kaneko's stellar Gamera trilogy in the '90s.

And though Higuchi would shortly go on to direct two Attack on Titan live-action films, their partnership would continue. Because in 2015, Toho announced they would team up to co-direct Godzilla 2016.

Part 3: 2016

Hideaki Anno has often thought of the apocalypse.

In an interview with Yahoo! News in 2014, he'd tell the interviewer he "sincerely thought that the world would end in the 20th Century," and that his fear of a nuclear arms race and the Cold War had heavily influenced Evangelion. However, his creative process isn't just permeated by man-made threats. "Japan is a country where a lot of typhoons and earthquakes strike ... It's a country where merciless destruction happens naturally. It gives you a strong sense that God exists out there."

This focus on earthly intervention by a divine presence is definitely a theme in Evangelion, but it also applies to Godzilla, a borderline invincible behemoth that was created to remind man of its mistakes. It's this kind of provoking thoughtfulness (among other things) that might have alerted Toho Studios of Higuchi and Anno's potential proficiency in re-igniting the slumbering Godzilla franchise. "[W]e looked into Japanese creators who were the most knowledgeable and had the most passion for Godzilla ...Their drive to take on such new challenges was exactly what we all had been inspired by," Toho would say of the pair.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

It was a few years in the making, though. After the creation of Evangelion: 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo, Anno fell into depression, causing him to turn down Toho's 2013 offer of the Godzilla project. But thanks to the support of Toho and Higuchi, Anno decided to eventually take them up on it. However, he did not want to repeat how he felt past filmmakers had been "careless" with Godzilla, stating that Godzilla "exists in a world of science fiction, not only of dreams and hopes, but he's a caricature of reality, a satire, a mirror image." Higuchi was also passionate about the project, saying, "I give unending thanks to Fate for this opportunity; so next year, I'll give you the greatest, worst nightmare."

Rounding out the NGE reunion with Shin Godzilla would be Mahiro Maeda, a character designer who would provide the look of Godzilla, and Evangelion composer Shiro Sagisu. Sagisu's music often includes motifs from Evangelion and the work of Akira Ifukube — who scored many classic Godzilla films — and is a great match for the monster. It's powerful stuff.

Anno's main concern was rivaling the first Godzilla, a film that remains effective to this day. So, in order to "come close even a little," he "would have to do the same thing." Thus, after over 60 years of monster adventures, Shin Godzilla became Godzilla's first real Japanese reboot, following a long line of films that were either direct sequels or had ignored the sequels to become direct sequels to the original. It would carry many of the same beats — monster arrives, people struggle to figure out how to stop it, they eventually do. The end. But unlike many Godzilla films, in which bureaucratic operations took a backseat to the scientists that would eventually figure out how to stop (or help) the Big G, they were front and center here.

And the depiction was often less than kind.

Instead of confident and sacrificial, the politicians found in Shin Godzilla are ludicrous in their archaic behavior, seemingly more concerned with what boardroom they're in than the unstoppable progress of the beast destroying their city. Most of their actions are played for comic relief, a tonal clash with the stark backdrop of the 400-foot-tall disaster walking just outside their offices. Multiple references are made to the Tohoku earthquake, the tsunami, and the Fukushima meltdown — including the waves that follow Godzilla as he comes ashore and the worry over the radiation Godzilla leaks into the land he travels across. One plot point even includes Japan grappling with the potential use of an atomic bomb on Godzilla from the United States, showing that over seventy years after the end of WWII, nuclear annihilation remains a terrifying prospect.

In the end, only a team organized by a young upstart that's mostly free from the processes of his slower, befuddled elders can save the day. That said, "save" isn't really the right word. Echoing Anno's statement that Japan is "a country where merciless destruction happens naturally," Godzilla is only frozen in place, standing still in the middle of the city, a monstrous question left to be solved. Whether it's Godzilla or a disaster like Godzilla, it is a problem that you must deal with, prepare for, and rebuild after. It will always be there.

That said, the film isn't just a parody of quivering government employees out of their depth in the face of a cataclysm (distrust in the goodwill of authority figures is a theme also omnipresent in Evangelion). It's also a really, really rad monster movie. Godzilla is a scarred, seemingly wounded creature, his skin ruptured and his limbs distorted. He is not action-figure ready, even as he evolves into forms more befitting of total annihilation. As the Japanese military increasingly throws weaponry at him, he transforms to defend himself, emitting purple atomic beams from his mouth, his back, and finally his tail. Higuchi and Anno's direction is often awe-inspiring, whether the camera is tilted up to capture Godzilla from a street-level view, or panning around a building to face him head-on. Godzilla feels huge.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

Its this combination of ideas and execution that would cause Shin Godzilla to sweep the Japanese Academy Awards in 2017, and, excuse my pun, absolutely crush it at the box office. But an incredible movie wouldn't be the end of it. In fact, while Shin Godzilla was a successful Anno creation, it hadn't yet gone to battle with Anno's other most successful creation.

Not yet anyway.

Part 4: 2018

A few months before Shin Godzilla's release, Toho announced a "maximum collaboration" between Godzilla and Neon Genesis Evangelion, a team-up that first manifested itself in art and crossover merchandise. Art with the logo for NERV (the anti-Angel organization from Evangelion), with the fig leaf replaced by Godzilla's trademark spines showed up on a subsite for the Shin Godzilla film.

Meanwhile, video game developers Granzella and publisher Bandai Namco worked on City Shrouded In Shadow, a game where you played as a human trying to survive attacks from various giant beings, including some from the Godzilla universe and some from Evangelion. And though this wasn't specifically tied to Shin Godzilla — Godzilla looks much more like his design in the '90s series of movies, a monster style that was the go-to branding look for years after — it did make the idea of the two franchises co-existing in similar spaces a little less alien.

The big one came in 2018 when Universal Studios Japan declared that the following summer, it would be home to a meeting of the two titans in "Godzilla vs Evangelion: The Real 4-D." This ride/theater experience would give audiences a firsthand look at a clash between the EVA units and Godzilla. However, just as the horror of the original Godzilla had been diluted through various sequels that saw him becoming Japan's protective older brother, and just as the crushing melancholy of Evangelion feels a little less sad when you see Rei posing on the side of a pachinko machine, this ride would also be a reframing experience.

Godzilla is a threat, at first, as the Evangelion units zip around, blast him, and try to drop-kick him. But then, out of space, Godzilla's old three-headed foe King Ghidorah emerges. The golden space dragon provides a common enemy for the group and they work together to eliminate it. Godzilla, seemingly forgetting why he showed up to the ride in the first place, trudges back into the sea. He is now a hero, his spot as Earth's Public Enemy #1 seemingly neutered.

To this day, news of theme park attractions that bear the Shin Godzilla design consistently pop up, including one ride where you can zip line into Godzilla's steaming open mouth! But Toho doesn't seem open to a live-action sequel that many see as the obvious next step (though they would produce a trilogy of anime films that take place in a different monster timeline). Instead, they opted for beginning a kind of Godzilla shared universe, like the extremely popular Marvel Cinematic Universe. And Anno and Higuchi have moved on to their next revitalizing effort: a reboot of Ultraman.

Wes Craven, the director of A Nightmare on Elm Street once said, "You don't enter the theater and pay your money to be afraid. You enter the theater and pay your money to have the fears that are already in you when you go into a theater dealt with and put into a narrative ... Stories and narratives are one of the most powerful things in humanity. They're devices for dealing with the chaotic danger of existence." The creators at Toho certainly gave people that with Godzilla, just as Anno did with Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Image via Amazon Prime Video

But horror films are also entertainment, and soon these monsters are sequel-ized and commodified, losing their edge to the point that new minds are brought in to reboot them and help them move forward. It's a process we've repeated since people began telling stories to one another thousands and thousands of years ago. They help us confront the worst aspects of ourselves and of our worlds. It's what makes them vital. We need them. Like the next evolution of monsters sprouting from Godzilla's tail in the final frame of Shin Godzilla, the horror genre reaches out, grasping for fears that we have and fears that will one day come.

For more Crunchyroll Deep Dives, check out Licensing of the Monsters: How Pokemon Ignited An Anime Arms Race and The Life And Death Of Dragonball Evolution.

Daniel Dockery is a Senior Staff Writer for Crunchyroll. Follow him on Twitter!

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features.

Source: Latest in Anime News by Crunchyroll!

Comments

Post a Comment