There is no clear blueprint for constructing a work like Cowboy Bebop. If there were, it would not be so beloved, nor would it remain standing as a “genre unto itself” all these years later. Director Shinichiro Watanabe and writer Keiko Nobumoto created something distinct, something only possible through a combined fascination with cinema and mastery of animation. At the same time, Bebop’s influences are clear to see. It certainly feels as though Watanabe doesn’t hide his sources, but rather displays them proudly, celebrating the films he’s loved even as he charts his own path.

All images via Netflix

Watanabe isn’t some unreachable genius of narrative form; he’s simply a cinema buff in an anime director’s chair, happily applying the lessons of cinema history to his own work. When you pick at the seams of Cowboy Bebop, you begin to recognize Watanabe’s Dr. Frankenstein-esque talent — but oddly enough, this does nothing to dissipate Bebop’s magic. Truthfully, the act of borrowing and recombining ideas from your influences is more or less the essence of creativity itself. Greatness comes not from true “originality,” but from cribbing widely and gracefully enough that the distinction between invention and pastiche feels meaningless.

Cowboy Bebop stands as a testament to that fact. It is an amalgam of 60 years of cinema history that, collectively, feels as fresh and essential as its disparate influences. Bebop’s debt to its inspirations goes far beyond aesthetic or form; by tapping into the genres that electrified previous generations, Watanabe is also able to evoke the social conditions and anxieties that inspired them, instilling Bebop with both the smokey malaise of post-war anxieties and the joyful energy of kung fu cinema. Today, I’d like to sift through just a few of Bebop’s cinematic debts, demystifying Watanabe’s masterpiece and demonstrating the cruciality of cinema scholarship along the way.

Many words come to mind when describing Cowboy Bebop, but above all of them, the show has an undeniable, effortlessly confident sense of cool. That’s no surprise, given the show draws heavily on some of the most historically stylish cinema genres, from noir and westerns to blaxploitation and Bruce Lee’s performances. But throughout history, I’m not sure any film genre has possessed such a self-conscious sense of modernity and “cool” as the French New Wave. We’ll start there, and wind our way toward Bebop’s other ancestors along the way.

The French New Wave’s influence is clear even in the titles of Bebop’s episodes. The essential Jean-Luc Godard feature Pierrot le Fou actually provides the title for one of the show’s most famous episodes — with his uncertain swagger and fatalistic sense of alienation, that film’s protagonist could be seen as a partial model for Spike, as well. Additionally, Pierrot le Fou’s early party sequence also likely inspired Bebop’s acclaimed title sequence, with its color-coded parade of anonymous guests clearly matching the style of the “Tank!” animation. As I said, Watanabe doesn’t make too much effort to hide his sources.

New wave cinema’s influence on Bebop appears to extend beyond mere visual and textual nods. On a more fundamental level, the films of Godard and others were stripping back the pretension of earlier film eras, presenting films that often felt scattered in their narrative pretensions or erratic and fluid in their formal technique. Characters stumble through worlds and situations they seem fundamentally ill-prepared for, stylish in their tumbling, all the more so for their lack of control. The idea of a “grand narrative” is ridiculed and discarded, the naive assumption of a premodern age. Modern life is not so simple as to provide such things.

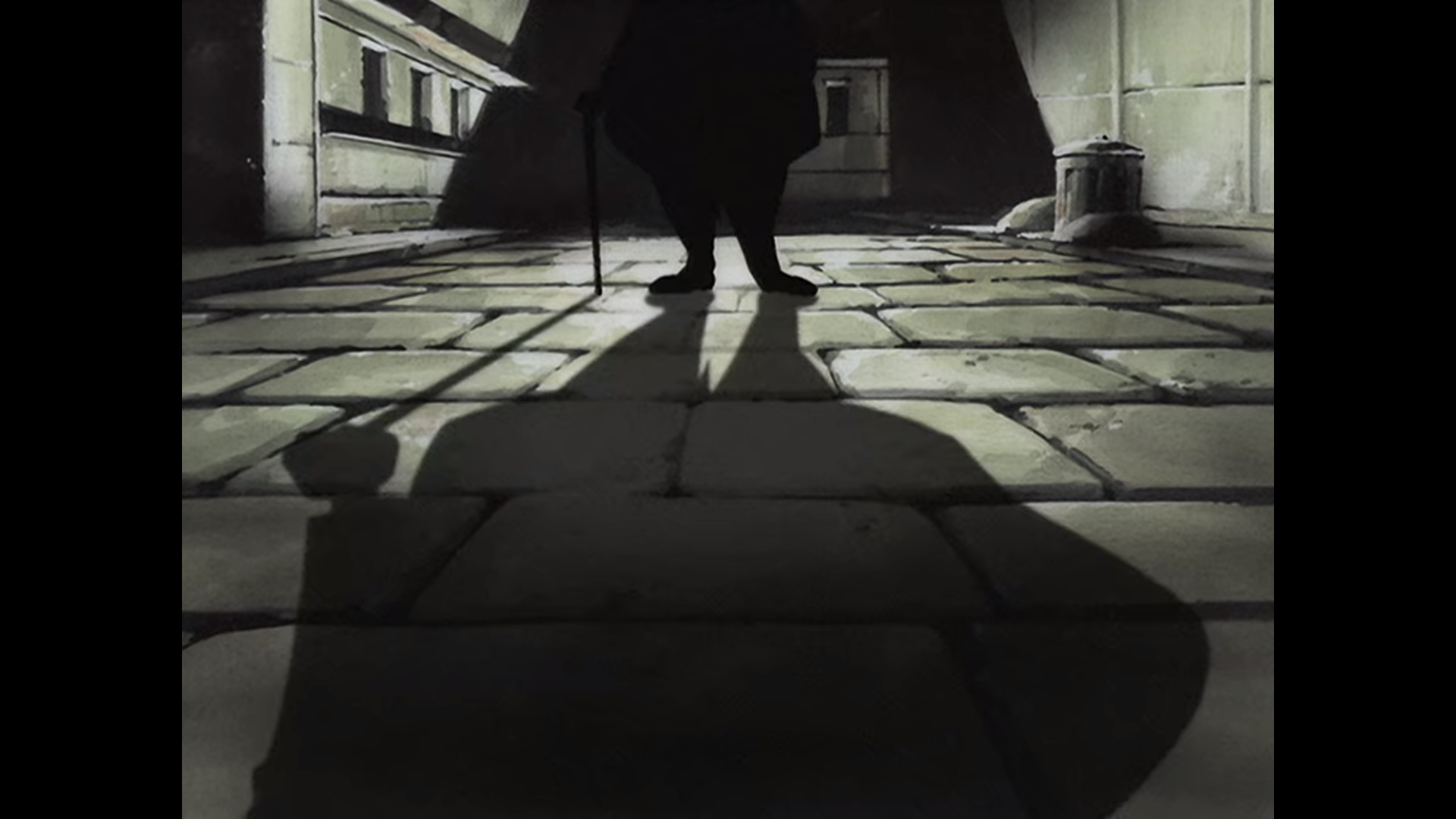

The new wave auteurs were bursting out against the staid formalism of their predecessors, finding it both artistically unsatisfying and ill-equipped to capture the realities of a new and confounding world. There was a pretty simple reason for this revolution of form: French New Wave is an emphatically post-war genre, a genre borne out of global wars that shook our foundational beliefs in peace and order. Its protagonists often seem aimless because the world they inhabited felt unmoored, with no clear indication the future would be any greater or more coherent than the past. When the cinematic old guard failed to revise their vision for this world of incoherence, Godard and his contemporaries took it upon themselves to replace them, discarding careful formalism for bold innovation.

These instincts, these visual and dramatic indicators of a world in disarray, carry through to Cowboy Bebop. Bebop’s world is strange and unstable, unfamiliar even to its occupants, all of them stuck reminiscing on the world of before. Constant focus on folks panhandling or picking pockets emphasizes the poverty of this era; with so much focus on incidental city folk with no dramatic importance, you could even draw a line from sequences like Knocking on Heaven’s Door’s opening back to the Italian neorealists. Similar to the new wave films, Bebop seems to possess a sense of dissatisfaction with the aesthetic tools that its creators have been presented with. Watanabe may not be inventing dramatic forms whole cloth like the new wave masters, but he is mixing and matching pieces to create a form of his own design, the alleged “new genre unto itself” of the OP.

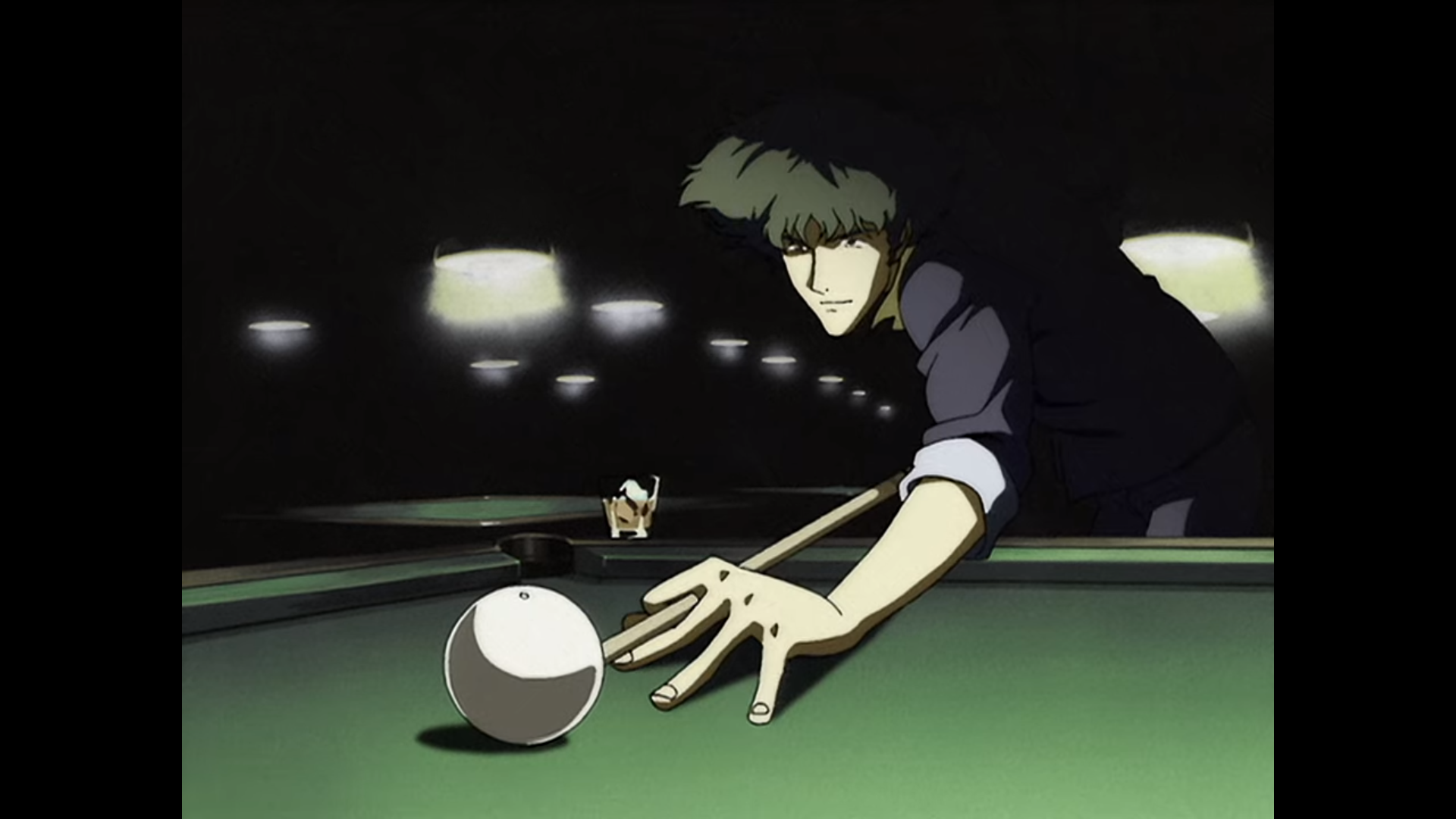

Equally important to Bebop’s aesthetic, and complimentary to the new wave influences, stand the show’s noir influences. Noir likely composes the greatest contribution percentage-wise to Bebop’s overall formula, as both the show’s episodic detective dramas and overhanging Vicious/Julia drama fit squarely in noir’s narrative traditions. Cleaning up the loose threads of the larger criminal syndicates, straying just outside the law in your detective work, operating from an ambiguous morality but ultimately trying and failing to bring some brightness to the world; it’s all classic noir stuff, and Watanabe’s team executes it with grace. Additionally, the bold, take-no-prisoners femme fatales of films like Double Indemnity provided a unique blueprint for feminine power and agency, which when combined with the show’s more comedic influences results in the inimitable Faye Valentine.

Beyond noir’s obvious narrative influences on Bebop, the genre’s tonal and stylistic influences might be even greater. Like new wave, noir is a post-war genre, similarly tethered to the global culture shock that was World War II. In the face of that war, old systems of righteousness felt ill-fitted for our fallen world. Those who would administer justice are equally scarred, former soldiers or policemen who have given up their naive dreams of setting the world right and are now only looking to make a buck. You can see how this worldview maps to Bebop: from Spike’s “one eye in the past” to Jet’s disillusionment with the police to Faye’s general displacement from the world, all of Bebop’s heroes have been equally scarred by their past and cannot imagine a brighter future.

The very presence of bounty hunters as a concept emphasizes the dissolution of social order in Bebop’s world. The show exists in a specific moment of civil crisis, and as it ends, so does it seem its era is also ending. While sequences like the Real Folk Blues ending, the entirety of the Julia/Vicious saga, or Ganymede Elegy traffic heavily in the visual signifiers of noir cinema, the show overall is bathed in the worldview of noir. Both Spike and Jet see their glory days as long behind them; in fact, it is in large part their fatalistic indifference to the future that makes them seem “cool.” Bebop’s heroes have already been broken by the world, their sense of jaded fatigue informs their every action.

A purely noir/new wave-influenced anime would make for a dynamite show in my view but it’d also be a pretty sober and disorienting one. Watanabe added a great deal of sweetness to the broth through his later genre influences, ranging from Bruce Lee’s dynamite performances to Blaxploitation, westerns, and anime’s own contributions.

It’s highly doubtful that Watanabe chose to stylize Spike as a Jeet Kune Do master by accident. Bruce Lee’s signature style of martial arts is distinctive and graceful, a seemingly perfect fit for the lanky and perpetually nonplussed Spike. Watching him “accidentally” stumble his way through half a dozen guards is a work of beauty that combines as much farce as force — but on a more metaphorical level, Lee’s self-designed system of taking what works from various fighting forms without feeling overly beholden to their rules seems like it’d appeal personally to Watanabe. Bebop, too, is a work of skillful yet irreverent collage; you get the feeling that Bruce Lee would approve of Watanabe taking his own genius in turn, and then setting his accomplishments in the context of a noir-soaked, John Woo-derivative gunfight.

In a similar vein, Bebop’s clear debts to Blaxploitation cinema reflect their common predilection for irreverent collage. Blaxploitation films combined action, crime, martial arts, westerns, and much else to dramatic effect, taking the staid genres of classic Hollywood and retrofitting them to righteous, bombastic stories of people who’d been largely ignored by cinema. The films were hits across demographics, and in spite of their sometimes exploitative content, brought Black concerns and lives to the big screen in a way like never before. I imagine Watanabe grew up absorbing these vivid lessons in cinematic medley, and Cowboy Bebop’s effortless bounding from melodrama to martial arts to comedy and back reflects Watanabe’s understanding of this technique. Meanwhile, the streets and alleyways of Bebop’s world are absolutely brimming with characters plucked straight from the genre, perhaps most memorably in Mushroom Samba.

With all these diverse film influences in attendance, you might begin to wonder how the “cowboy” part fits into Cowboy Bebop. Fortunately, westerns actually share a fair amount of tonal DNA with Bebop’s other mid-century cinematic influences. Though the early golden age westerns often exhibited a generally optimistic perspective, by the time you get to classics like John Ford’s The Searchers, the genre is tinged with a sense of inevitability and regret. Like Spike Spiegel, The Searchers’ John Wayne can only gaze in at the peace of post-war life, knowing it is not to be his. And by the time we reached the revisionist and spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone and others, the inherent righteousness of the noble cowboy had long been discredited. Like noir and new wave, many of the best westerns are filtered through the post-war malaise of the reconstruction era, filled with old soldiers who can’t go home again — another easy parallel for the ambiguity of Bebop.

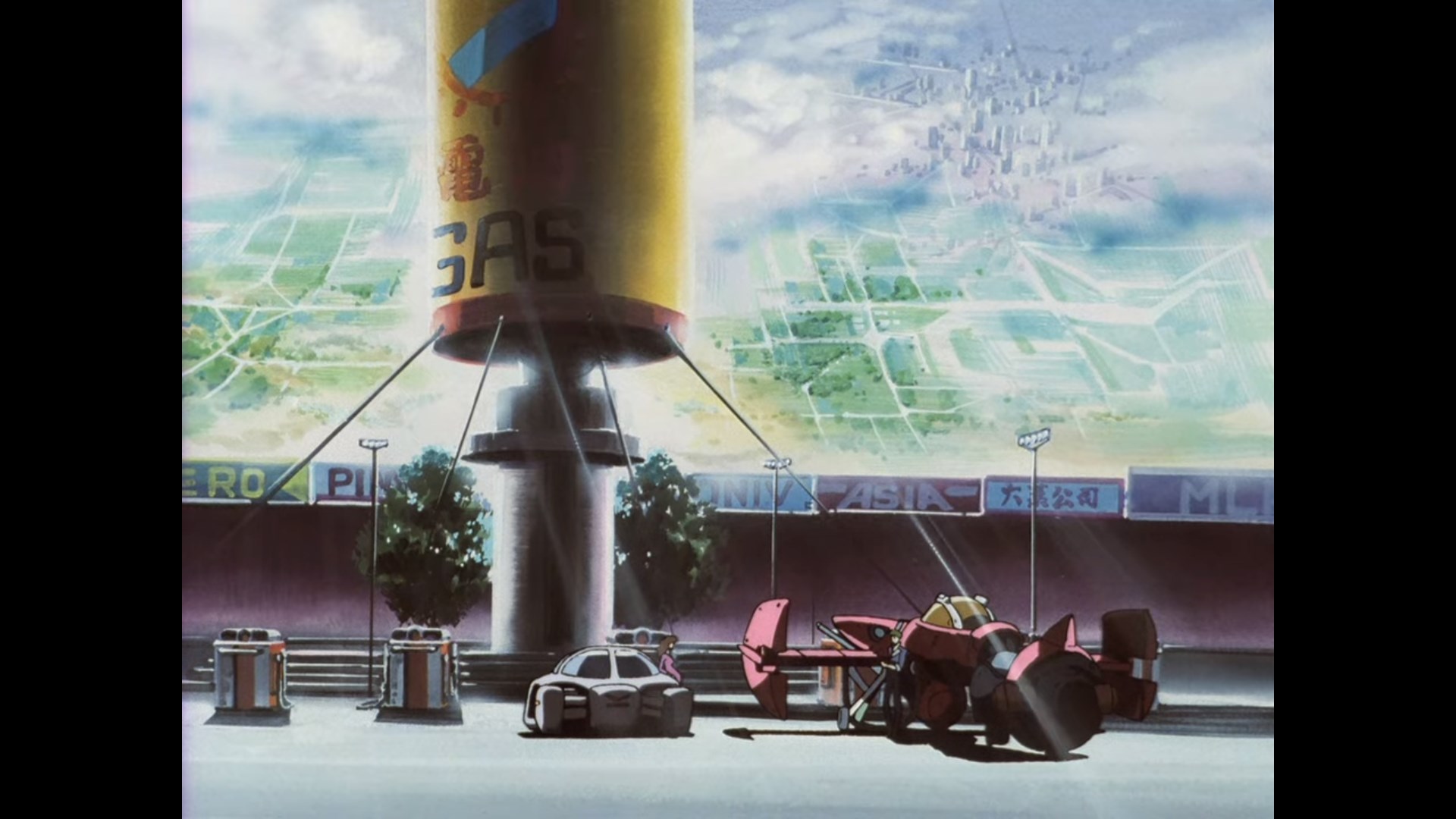

Westerns’ influence on Bebop extends to both its worldview and aesthetic. While the cold, urbanized beauty of noir and neorealism clearly influences Bebop’s dilapidated cities, it is the vast skies and lonely deserts of the western that seem to inform its open spaces. Westerns prioritize wide shots and stillness, letting the vast canopy of the stars and night howls of the prairie overwhelm their insignificant protagonists. For Bebop, the lonely call of the western is a necessary counterbalance to its more energetic influences, informing many of its moments of peace and reflection, while sharing a sense of “last tour” fatalism that aligns it with Bebop’s general ethos. Of course, there are more direct parallels within Bebop’s many stories, like how Sympathy for the Devil winds toward its inevitable, High Noon-reminiscent conclusion.

There are plenty more influences we could dive into — anime’s general debt to Giallo cinema, more on-the-nose references like “the Alien episode,” what Watanabe carried over from his work on the Macross franchise. That said, my point here could not be further from “look at all these things that Bebop references.” Simply referencing a secondary work of media does nothing to improve your own work. It is only by absorbing the lessons of that media, cataloging not just the choices of that work but the reasons behind those choices, that you can empower your own work. The history of cinema provides us with diverse aesthetic vocabularies, infinite tools to express the beauty of the world and the complexity of the human condition. The best directors are avid students of that history, who can employ stylistic tools from across cinematic tradition to achieve their own unique ends.

Rather than feeling unfocused, the broadness of Watanabe’s inspirations allows him to construct a new aesthetic with a profound clarity of purpose, one that still embodies the diverse strengths of its many, many influences. None of us are so creative that we’re likely to be inventing genres wholesale — even the greatest writers and directors will freely acknowledge ideas they’ve “stolen” from other sources. Making something truly “original” is next to impossible; far more important than originality is learning to steal broadly, to embrace a diverse array of influences and thereby instill your works with an aesthetic and vitality all its own. Cowboy Bebop’s richness should serve as a lesson to us all: the more broadly you consume and celebrate art, the more vibrant and unique your own creations will be.

Nick Creamer has been writing about cartoons for too many years now and is always ready to cry about Madoka. You can find more of his work at his blog Wrong Every Time, or follow him on Twitter.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

Source: Latest in Anime News by Crunchyroll!

Comments

Post a Comment