Image via Funimation

At the end of the twentieth century, anime was well on its way to becoming a pop-culture juggernaut in the United States. After Pokémon had established itself as a hot commodity and a force to be reckoned with, television executives were itching to grab their own piece of the anime pie. While Pokémon, Digimon, and other series ruled over Saturday mornings, Cartoon Network’s Toonami block of anime was carving out its own share of the audience. With an audience that skewed slightly older than the viewers of Pokémon, Toonami would be highlighted by one show in particular that proved to be a ratings hit: Dragon Ball Z.

Anime truly took off after Warner Bros. acquired the Pokémon license in 1999. In its first week under the Kids WB! umbrella, Pokémon would manage to hit a 3.9 rating (a percentage of how much a specific demographic of people is watching), reaching 3.1 million viewers by September, and Nielsen stating that “half the boys (ages 6-11) watching TV (at 10 a.m.) are seeing Pokémon” by that November.

Image via Pokémon TV

That’s not to say that the emergence of Pokémon was met with overwhelming positivity — many adults at the time were left baffled and confused at why Pokémon had instantly become one of the biggest properties in the United States in such a short amount of time. This included columns from syndicated columnists ("What 'Pokemon' sells so well (and the keyword here is 'sell') is adventure camaraderie and competition — where money rules," said Frazier Moore) and "What Parents Need to Know" articles alike.

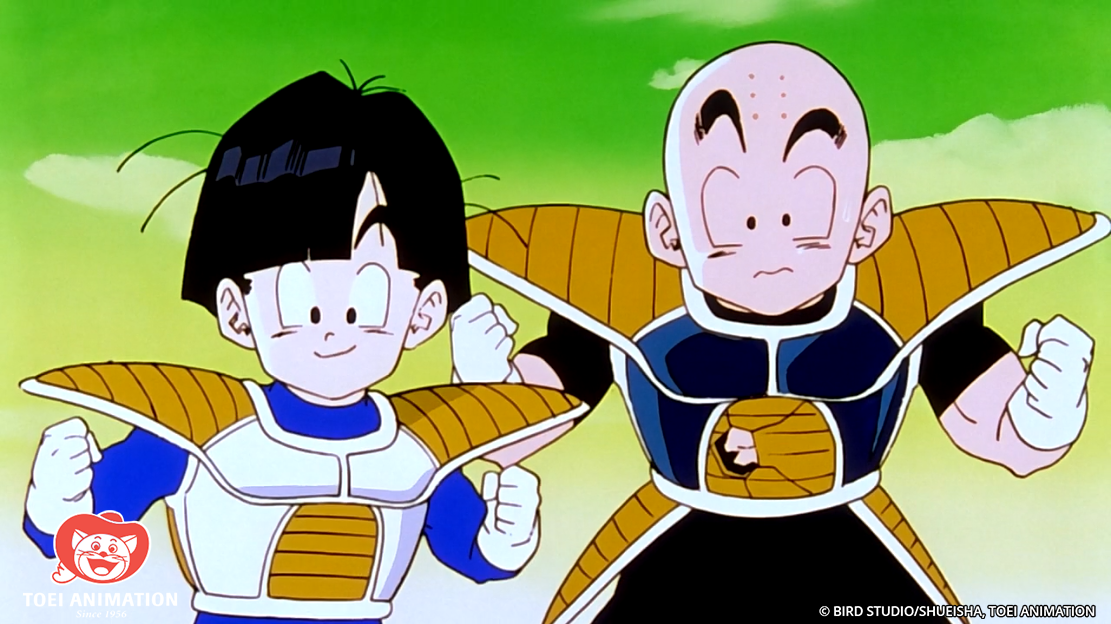

While Pokémon ruled over Saturday mornings, weekday afternoons also became a hotly contested battleground for anime, especially when a third network entered the fray. While it launched in 1997, Cartoon Network’s Toonami after-school block of programming began to shift to anime by including shows such as Dragon Ball Z, Sailor Moon, and over the years, many other series such as Gundam Wing and Outlaw Star. Despite being under the same Warner Bros. umbrella, Pokémon and Dragon Ball Z would soon become two of the top anime series in the United States for their respective networks.

Image via Funimation

Similar to Pokémon, Dragon Ball Z would begin to see a large rise in popularity beginning in 1999, with about 1.7 million households watching the show the week of September 30 and around 1 million in the kids 6-11 demographic on October 1, "the largest number in the network's history" according to The Wall Street Journal. The September/October time period would usually be when Dragon Ball Z would pick up steam with its ratings and viewership since that coincided with when new episodes would drop. In Fall 2001, Nielsen ratings would show Dragon Ball Z begin to rival WWF Raw is War and ESPN's regular Sunday NFL coverage.

The season premiere of Dragon Ball Z on September 16, 2002 became the most-watched show on TV for its key demographics, beating out everything from Digimon, The Simpsons, and CBS' Survivor: Thailand. "We anticipated good ratings for the new season," said Gen Fukunaga — president and found of Funimation — in a press release at the time. "But having the number one show for our target audience on all cable television is outstanding." The show's momentum would continue through the series airing new episodes in March 2003, with an estimated 933,000 children aged 9-14 watching the show during the week of March 17-March 23, and even through the series premiere of Dragon Ball GT on November 7, 2003.

Image via Funimation

With Dragon Ball Z being in the same stratosphere as Pokémon in terms of popularity, that also meant that it would get its fair share of detractors. While some critics were confused about the show in general, one of the main points of contention was the idea that the show was too violent for children, with one Wall Street Journal article exclaiming that the series is "A sort of Pokemon meets 'Pulp Fiction,'" and "Every weekday afternoon on Time Warner's Cartoon Network, characters age, die and get vaporized — suffering far worse fates than Wile E. Coyote ever did."

When you compare it to shows that Kids WB! and Fox Kids featured, it’s an apt observation. However, there was a distinct difference in the kinds of audiences that Pokémon and Dragon Ball Z were going for: Pokémon chased after a younger demographic, focusing more on the kids 2-11 age group, while Dragon Ball Z skewed higher toward tweens and teens, who might also chase after more adult media such as South Park and pro-wrestling with a prime audience of males 18-35.

While Pokémon and Dragon Ball Z were popularizing anime, they weren’t necessarily chasing the same goals for their networks, and that was especially true when it came to the philosophies of bringing anime over to American audiences.

Image via Funimation

In a 2001 interview in The Los Angeles Times, four of the biggest proponents of pushing anime in the United States got together to discuss how they present the Japanese medium to US audiences. One of the most notable parts of this interview is Donna Friedman, former executive vice president of Kids WB! and Al Khan, former chairman and chief executive of 4Kids Entertainment’s thoughts on anime. Khan discusses how 4Kids spends “a fortune on localization” from re-writing, re-scoring, and changing storylines to better suit American children. “We may spend another 50 percent of what we pay for them [in rights] just to localize them,” Khan said. Perhaps the most infamous part of this interview are his thoughts on Pokémon: “I don’t think the kids that are enjoying Pokémon know it’s animé [sic].”

Friedman also chimed in, “Kids don’t watch shows because of the style of animation.”

Inversely, Dea Perez, former vice president of programming of Cartoon Network, rebuked the idea that kids were unaware of anime or that extreme localization was needed for anime to be successful. About the Americanization of anime, Perez said, “We are desperately trying not to do that. We may tweak a couple of things for American audiences, but we don’t want to Americanize the shows at all. I don’t want to change this block to be like a toy block. I want it to be respectable.”

To their credit, Cartoon Network was certainly less egregious about aggressive editing, although they did air the heavily changed original English dub of Sailor Moon. For the most part though, outside of changing curse words, blood, certain opening and ending themes, or anything sexual, most of the shows that aired on Toonami didn’t have the same feel as a lot of the series that aired on Kids WB! and Fox Kids where they tried to rip out anything Japanese.

Image via Funimation

As someone who grew up during the anime boom, I can tell you first hand that my experience was very tied to the road between these two shows and their respective networks: I was first exposed through Pokémon, eventually found more shows through Kids WB! and Fox Kids, followed by Toonami, and then the internet to find any and all information about the shows I watched. What exactly caused me, and presumably a lot of kids, to make this transition? There was certainly this feeling that it just did more to amp you up. The fights, albeit sometimes too drawn out, were good for creating an atmosphere that wanted you to keep tuning in. The fact that it was filled with over-the-top, but very cool characters made for this immense combination that I couldn't get enough of.

There’s no denying that Pokémon was the number one anime to air on television in America from 1999-2003. Creating that amount of popularity and reach allowed anime to blossom in the United States in a way that it had previously never been able to. In a sense, Pokémon was the gateway show for fans to find other shows. Dragon Ball Z certainly benefited from this, becoming one of the top 3 anime to air during this time period, bringing with it a slightly older audience than Pokémon. Despite not reaching the same heights as Pokémon, Dragon Ball Z was still one of the biggest shows in cable for young adults and kids, making for an entire generation that was able to grow up with anime and still find enjoyment in the medium for years to come, as well as a time period they can look back upon fondly.

Image via Funimation

Were you someone that discovered anime around this same time or did you find anime another way? Let us know down in the comments below!

Jared Clemons is a writer and podcaster for Seasonal Anime Checkup and author of One Shining Moment: A Critical Analysis of Love Live! Sunshine!!. He can be found on Twitter @ragbag.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

Source: Latest in Anime News by Crunchyroll!

Comments

Post a Comment