If you were watching anime in the early 2000s, you know who Chiaki J. Konaka is. If you didn’t know him by name, you were probably familiar with his work on cult classics like Serial Experiments Lain or Digimon Tamers. With other influential series like Texhnolyze, Air Gear, and Mononoke under his belt, Konaka’s work has no doubt become some of the major hallmarks of anime available to English-speaking audiences in the early aughts.

That being said, Konaka’s work has a reputation for pushing boundaries against the convention of genre. An avid fan of horror, Konaka’s career began in live-action home video movies and television, where he explored topics such as the supernatural, extraterrestrials, and cults. By the time Konaka began working on anime, he already had made a name for himself appealing to a broad demographic. Having written everything from episodes for the popular Gakkou Kaiden (Ghost Stories) live-action television series to niche monster movies, he demonstrated a sharp eye for conventions of each particular genre and more importantly, why they worked so well. One thing has remained consistent throughout Konaka's career: his commitment to a uniquely private brand of horror.

Girl, Interrupted

Lain in her room (Source: Funimation)

One of Konaka’s most prevalent themes is being a stranger in a strange land. Whether for the sake of narrative convenience or simplicity, many of Konaka’s protagonists — regardless of the material's genre — often find themselves in bizarre down-the-rabbit-hole scenarios. The most famous example of this is, of course, Serial Experiments Lain, a cyberpunk series about a deeply isolated girl who discovers an internet world called “The Wired.” Following the later-end of a cyberpunk boom in Japan with directors such as Shinya Tsukamoto and Mamoru Oshii accumulating international cult-followings, the verge of the new millennia couldn’t have been a better time for Konaka’s most iconic work to debut.

Lain confronts the fake Lain inside The Wired (Source: Funimation)

In an entry on his personal blog, Konaka writes that Lain was initially planned as an interface-heavy game for the PlayStation, which didn’t offer him many scenario writing opportunities. It was decided a 1998 late-night anime would be produced to promote the game, which would offer Konaka ample space to explore Lain’s world with fewer constraints. This approach to scriptwriting led to Lain’s infamously ambiguous story structure, which centered on Lain gaining access to The Wired and the various anonymous organizations vying for power within it. Unlike the PlayStation game, which relied heavily on players navigating a complex system of computer files about Lain, Konaka’s anime adaptation provides an intimate over-the-shoulder perspective. Lain, an introverted young girl, is quick to embrace a myriad of “other” Lain personae online. In episode 8 "Rumors," Lain returns to her own reality after confronting and attempting to kill one of the fake Lains in The Wired — only to find yet another "fake" Lain has somehow planted herself among her friend group. Whether it's a hallucination or not, it's a jarring moment of emotional whiplash and confirms Lain's fears aren't just online, but that her anxieties over her identity are becoming very real.

A "fake" Lain from The Wired among her real-world school friends (Source: Funimation)

For Lain, it becomes increasingly difficult to determine whether or not people like her or the internet's perverted image of her. The uncanniness Lain experiences isn’t a fear or helplessness to an almighty force or evil corporation like other cyberpunk stories. Rather, Lain’s biggest fears are these alarming encounters with her split virtual personalities — a stark reminder of who she may become after the inevitable collision between The Wired and reality. In the end, she is her own worst fear.

The Lovecraftian Connection

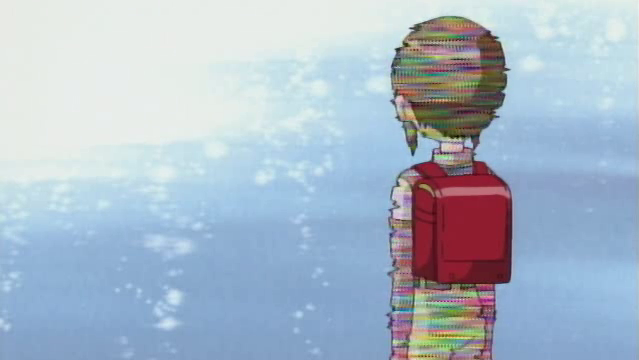

Gatomon watches Kairi "glitch" as she wanders across the street in a daze (Source: Hulu)

Although Konaka has certainly gained a reputation for his work flirting with cyberpunk, it’s by far no means the only format capable of unpacking these complicated themes of self-realization. Like many fascinated by the weird, Konaka is famously fixated on the works of American horror writer H.P. Lovecraft. It could even be argued Konaka is just a horror writer flirting with hybrid supernatural science-fiction. Much like the genre-omnivore his early writing credits would imply him to be, the way Konaka has approached a score of fantasy and cosmic-horror lend themselves to a far more liberal application of Lovecraftian tropes. This, of course, has given us some of the most unlikely mash-ups of thematic material, such as his episode “The Call of Dragomon” in Digimon Adventure's follow-up, Digimon Adventure 02.

The cave beside the mysterious Dark Ocean (Source: Hulu)

Obviously, a reference to Lovecraft’s 1926 short story “The Call of Cthulhu,” this episode was initially conceived as the starting point for an eventually abandoned story arc about the mysterious Dragomon entity. As if this didn’t make the episode interesting enough, it’s significantly darker in tone compared to the series’ typical upbeat mood. Kairi, an otherwise confident and outspoken girl, suddenly develops strange dreams and Lain-reminiscent behavior. Kairi eventually begins to develop hallucinations about being underwater and being watched. Eventually, she finds herself staring out at an ocean and exploring a dark cave — somewhere neither in the Digital World nor the real world. This is when things get uncomfortable — even in a reality where traveling between cyberspace and the real world is possible, there are still unknowable “in-betweens” yet to discover. Again, the slow unraveling of horror isn’t the reveal of Dragomon, but rather Kairi’s atmospheric aloneness in realizing the reality she’s taken for granted can suddenly be uprooted without warning. Classic existentialist cognitive dissonance. But, y'know. For the kids.

No One Can Hear You Scream in Cyberspace

Jeri is psychologically tormented by the D-Reapers and relives her mother's death in the hospital (Source: Hulu)

After Digimon Adventure 02, Konaka would continue exploring this theme of protagonists inadvertently entering “new worlds” and having to reconcile their identities as a consequence. Like Lovecraft’s characters uprooted by the mere knowledge of cosmic horrors in isolation, Konaka’s characters must sink or swim when it comes to reality-shattering revelations. Konaka’s writing on 2001’s Digimon Tamers strongly flirts with these ideas, going beyond a simple “deconstruction” of the series’ basic premises toward a more psychological direction. Although Tamers' main protagonist Takato is himself an idealistic fan of an in-universe Digimon franchise, Tamers doesn’t forego the very real consequences of abruptly being spirited away to a violent new world. The kids aren't simply away at summer camp anymore — after a few dozen encounters with god-like creatures, the mental strain begins to slowly creep up on the DigiDestined. Rather than escaping without consequences, Konaka’s DigiDestined have to face the music and realize their escapist fantasies about Digimon aren’t what they imagined. This version of the Digital World isn’t morally flat, but something borderline Eldritch that becomes fully realized in the series finale.

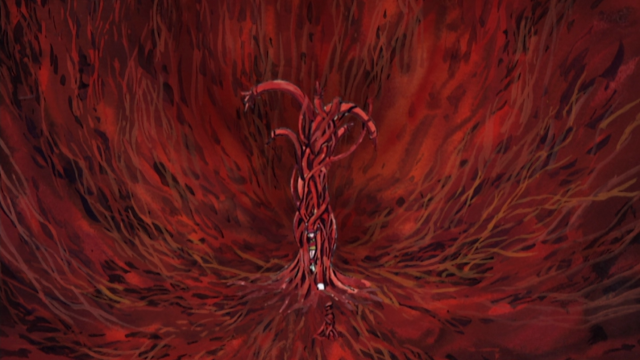

Jeri captured by the D-Reapers with Calumon (Source: Hulu)

In Tamers' climatic arc, Jeri, Takato’s eccentric classmate and fellow Digidestined, is abducted by man-made programs called “D-Reapers” as they take over the city. The D-Reapers, who intend to eliminate both the human and Digimon world, attempt to transform Jeri into the “Mother D-Reaper” by channeling the traumatic memories of her mother’s death. As notorious as Tamers' ending has become, it's perhaps not as brutal in the broader context of Konaka’s work. While captured, the D-Reapers keep Jeri in a Nyarlathotep-like cyber-flesh tower — similar to Tsukamoto’s half-man, half-machine character from Tetsuo: The Iron Man. Jeri doesn't have the intermediary of a Digimon to help — her partner Leomon is gone — and therefore has to face the unintelligible cosmic-cyberpunk D-Reapers alone. The “real” Jeri is momentarily gone. Like Lain’s lost identities in The Wired. Again, an adolescent protagonist must face the horror of losing one's self in a world with no logic. For a moment, she becomes truly hopeless, believing that this is "fate," recalling the phrasing doctors used described her mother's death. Thankfully, Jeri recovers and reunites with her friends as the equilibrium between the Digital World and reality are stabilized. But the point still stands: Our most intimate fears far surpass anything else we can face in the most alienating of scenarios.

The Petty Exorcist

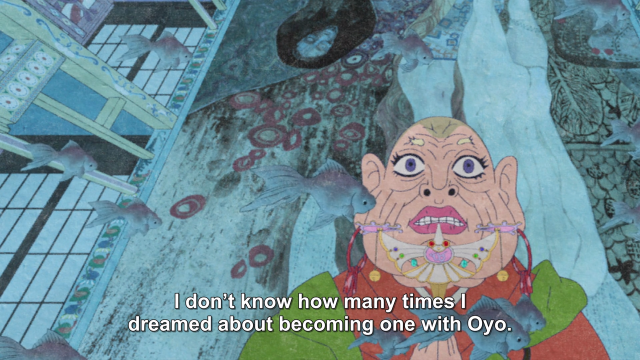

Genkei confides to The Medicine Seller aboard the ship

Beyond flights of cyberpunk cognitive dissonance fancy, Konaka’s work on the 2007 series Mononoke draws a more direct line back to his origins in Japanese horror cinema. A spin-off of the Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales series, Mononoke focuses on a pointy-eared man known as the “Medicine Seller” and his mission to terminate malicious spirits called “mononoke” across feudal Japan. Konaka’s story-arc “Sea Bishop” pays homage to classic funayūrei (boat spirit) ghost stories with a whodunit twist after someone sabotages the ship's navigation. Having wandered into the Dragon Triangle, a dangerous part of the Pacific Ocean full of evil spirits, a monk aboard named Genkei is suspected of the deed. Rather than immediately deal with any suspected mononoke, the Medicine Seller must decipher the true reason Genkei led them astray — his challenge isn’t an exorcism, but rather distinguishing petty human lies from truths. Genkei explains he did so to free his sister's spirit, who was supposedly sent to sea in his stead as a human sacrifice. Up to this point, Genkei’s intentions seem noble until his manipulative past is revealed: He had been fighting incestuous thoughts and guilt for years, having only become a monk to cope with his feelings. His sister died in vain.

The True Face of Horror Is Your Own

After the Medicine Seller reveals he knows someone is lying on the ship, Genkei gives his confession

Satisfied with Genkei's understanding he has been living a lie, the ship's mononoke finally emerges to be slain. It’s only this expulsion of a private fear that allows the Medicine Seller to finish his work. This time, no one is being manipulated by spirits or supernatural entities — all that remains is one person's terrifying inability to see beyond the lies they forced themselves to believe. The "real" you is worse than anything you can imagine.

Konaka’s fiction rarely gives us easy answers. While his work may seem oblique and impenetrable at first, these are fundamentally stories about people’s biggest fears being themselves and what they believe they know to be true. Although the novelty of being whisked to a fantastical world is alluring, Konaka doesn't downplay the expected alienation and anxieties of his characters. For as wide-ranging and genre-agnostic as his many series are, they never lose track of what fundamentally makes this flavor of horror unique: an embrace of the uncanny, the bizarre, and unflinching honesty.

What spooky anime gives you nightmares? Let us know in the comments!

Blake P. is a weekly columnist for Crunchyroll Features. Impmon did nothing wrong. His twitter is @_dispossessed. His bylines include Fanbyte, VRV, Unwinnable, and more.

Source: Latest in Anime News by Crunchyroll!

Comments

Post a Comment